Sexism covers all individual or collective behaviour that legitimises and maintains the domination of men over women. It manifests itself in words and behaviour, from the most apparently harmless – known as ordinary sexism – to the most serious, such as rape or feminicide.

Gender stereotypes

Sexism is based on stereotypes that perpetuate gendered roles and attitudes, differentiating between men and women. These stereotypes are deeply rooted in our education and are present at all levels of society, whether in the public space, the workplaces, leisure activities, political life, institutions, the media, etc.

These stereotypes, although unfounded or self-fulfilling, continue to be ingrained in our brains. It is commonly believed that women drive badly, yet the facts show that they cause far fewer accidents while driving just as much. Or that they’re talkative, while studies show that women talk just as much, if not less, than men in the private sphere and much less in the public sphere.

Sexism is systemic

Sexism does not consist of isolated, individual and deviant acts, but of repeated and structural behaviour, deeply rooted in the organisation of society. To quote this report, sexism ‘emerges from several social structures that are interrelated and feed off each other. It is rooted in historical, economic, political and social causes. It is widespread and persistent, deeply rooted in social behaviour and social organisation. It is usually unchallenged and acts indirectly. It is invisible. It is little aware of and maintained by social and institutional structures. It is developed and maintained on the basis of laws, policies, practices, stereotypes or prevailing customs, in all spheres and at all structural levels of society, in both the public and private sectors’.

‘It’s okay, it’s just a joke!’

#boohoo #youcannotsayanythinganymore #itwasbetterbefore

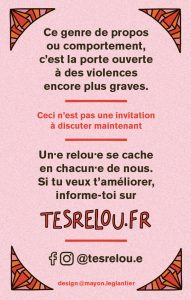

There is a continuum between seemingly innocuous comments and behaviour and more serious violence. Telling or laughing at a sexist joke may not seem very serious in itself, but part of its violence lies in its repetitive and widespread nature. A sexist joke is not just a joke, it adds to all the others that have gone before. In addition to its intrinsic violence, it legitimises and perpetuates an ideology that has serious consequences for all gender discriminated people.

For example, jokes about blondes perpetuate in the collective imagination the idea that women are less intelligent and more vain than men. This leads to differences of treatment in personal and professional life and problems of self-esteem, from a very early age.

It’s important to take this into account when it’s pointed out to us that a particular gesture, comment or behaviour is sexist (or even simply oppressive, as this can apply to any other systemic oppression).

The danger of benevolent sexism

When we think of sexism, we first think of its hostile form, imbued with misogyny, expressing contempt and hostility towards women and other gender discriminated people, very well represented by the ‘incel’ movement. Hostile sexism is generally directly recognisable as such.

But there is a more insidious form, benevolent sexism, in which women are seen as fragile beings whom men have a duty to protect. Children’s fairy tales are full of stories where a knight or a charming prince comes to the rescue of a damsel in distress. Unfortunately, this trope does not disappear as we grow up, one of the most traditional expressions being chivalry.

Even if it can be part of strategies of domination, benevolent sexism is generally well-intentioned, which is why it is often difficult for a gender discriminated person to denounce it, at the risk of being seen as difficult or even aggressive. While women do benefit from favours, they cost men relatively little (like holding the door or paying the bill), and keep them in an inferior position (if you have to help them, it’s because they’re not capable) and dependent (how can you learn when someone else is doing it for you).

The end of sexism?

A lot has changed in recent years, thanks in particular to feminist and intersectional struggles. Sexist and sexual violence is increasingly visible and denounced, and legally, women have the same rights as men. This leads some people to say that we are now witnessing the end of sexism, and of the patriarchal system in general. But that’s without taking into account the ‘backlash’, theorised in the 1990s by Susan Faludi. Every feminist advance is followed by a conservative and reactionary movement that rolls back women’s rights. And this can have serious consequences, such as the annulment by the US Supreme Court in 2022 of the Roe vs Wade ruling, which had recognised the right to abortion in the United States since 1973.

This phenomenon is also at work in France today. According to a recent report by the Haut Conseil à l’Egalité entre les femmes et les hommes, there has been a return to traditional values among men aged 25 to 34. For example, 34% (+7 points) of men think it is normal for women to stop working to look after their children, while 37% (+3 points) consider that feminism threatens their position. More than their high figures, it is the increase in these percentages that is worrying. Unfortunately, sexism is far from being a thing of the past.

Reverse sexism, or why it doesn’t exist

Feminism has become a regular topic in the media, especially since #Metoo. What could be more normal when you consider how far we still have to go and that it still affects 50% of the population? But following the progress – albeit relative – made on certain rights, some people are quick to trot out the argument of so-called ‘reverse sexism’.

Men can be discriminated against when they do not conform to the social roles expected of their gender. However, this discrimination is not based on the assumption that men are considered inferior to women, but always on the assumption that women are considered inferior to men, with whom they are then associated. In a patriarchal system, there is nothing worse for a man than to be associated with a woman. This is individual discrimination, not a systemic ideology. Conversely, a man who conforms to these gender stereotypes will have nothing but social gain.

Many of the injunctions made to men can be a source of suffering: be strong, don’t cry, don’t show your weaknesses, etc. But make no mistake, these injunctions are an integral part of the patriarchal system that feminist movements are fighting against. And it is by responding to these injunctions that a man becomes an oppressor.

Male domination is deeply rooted in our society and sexist representations are still the norm. If we don’t work to deconstruct them (the famous red pill in Matrix), we don’t even notice them any more. On the other hand, we will immediately notice something that is outside the gendered norms. For instance, women are seen as talkative because we’re so used to their silence that we notice more when they talk. More equality and representation in the media does not mean that we have finished with patriarchy, and even less that we are entering a matriarchal system.